“I don’t get vegans…why they need to copy the real thing? If they don’t want to eat meat why they need vegan sausages?”

I bet you heard this phrase, or something along these lines, many times by some critical carnivore friend, complaining about the (many) faux-meat veg product ranges that, for some time now, are occupying more and more space in mainstream retailers’ shelves.

The examples are plentiful and they quite convincing in reproducing the appearance, the smell and (to a point) the taste of “real” (real is in intentionally in quotation marks, keep reading to find out why) meat. This particular product category ranges from faux-mincemeat, ready to cook plant based burgers and sausages, up to the newest vegan boiled eggs, just recently developed by an all-female team of researchers at the University of Udine.

Could you tell the difference? Not just by looking for sure! and, by the way, those are cholesterol free! (© Università deglistudi di Udine)

When I hear the aforementioned complaint I always find myself thinking “why not?” and became fixated on the notion of “real thing”: what is the real thing? what does it make it more real than the other? Especially in the case of a manufactured, ready to cook, product such as a hamburger or a frankfurter, which doesn’t resemble nothing of the cow(s), the pork(s) or the chicken(s) it’s made from anymore and it is as equally processed as its vegan counterpart.

The short answer? Nothing.

The only difference is that the pork one came first and we (or at least the majority of us) are used to it.

This bias is fundamental to connected to the concept of food familiarity, which pervades and dictate our behaviour toward food consumption. Familiarity in food research is defined, as:

“the number of product-related experiences that have been accumulated by the consumer.”[1]

Trying to clarify a bit more, this concept refers to the level of knowledge that a consumer about an envisioned product and its characteristics but also to the degree of confidence such consumer has in their ability to evaluate its quality [2]. So, familiarity, as a consumer behaviour concept, is not as simple as it may appear at a first glance.

It is the result of the many inputs that the consumer absorbs while experiencing a product (or a brand). It’s the sum of the multitude of sensory stimuli (taste, smell, texture, etc…), the assorted chunks of knowledge that the food product elicits in the consumer mind (that goes form nutritional values, cooking methods, to happy memory linked to the product), and even just mere exposure to it[4].

The concept of familiarity is applied to many aspects of the food decision process: its influence starts even before the purchase in the form of the reassuring logo and colour code of a known brand. That is one of the reasons, for example, of why many off-brands resemble closely the most diffuse ones.

It is also the main mitigatory factor of food neophobia, which means the aversion toward trying new food, especially present in kids[4]. That’s why many food products marketed toward children try to embed some familiar element or try to hide some traits diverting the child attention: see dinosaur chicken nuggets or the goldfish crackers.

why the h*ll they must be shaped like fish? I don’t understand it at all, they taste like cheese anyway! (see? nobody is safe from this kind of complaining, not even me! )

Also, Familiarity has a moderating role toward trust, which in turn is attenuating factor of perceived risk (it another easy yet complex concept regarding consumer behaviour).

“Familiarity with a product has a critical role in aiding comparisons between products and the consequent choice of purchase”[3]

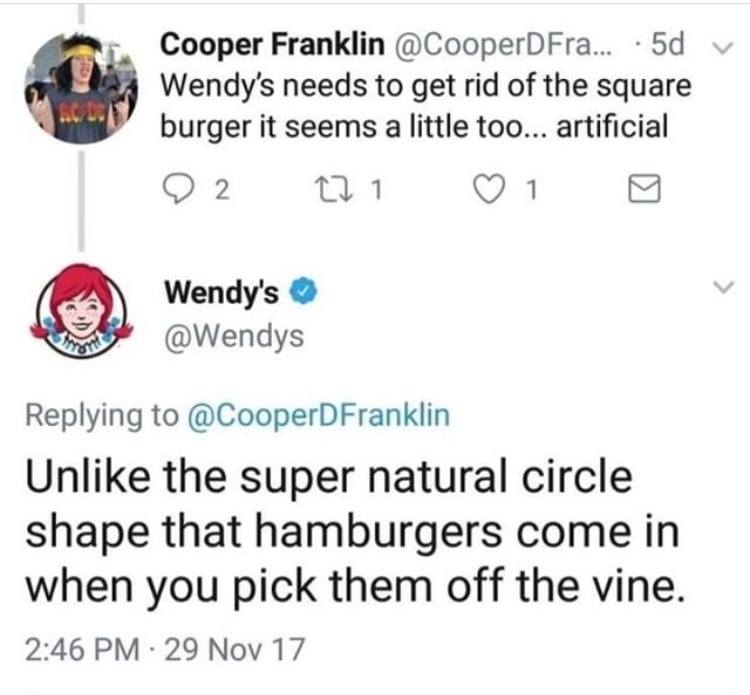

These are the reason why some degree of familiarity in novel products, as in the case of vegan meat substitutes (but also, for example, for edible insects), is fundamental to their success when they hit the market![5]Which perfectly explains why Beyond Meat and Impossible Food, producers of what is arguably the most successful novel food of the last few years, directed all of their research effort toward re-creating the same sensory experience of real meat burgers, in their plant-based products, to pass the so-called “carnivore test”. Mission accomplished so well that now they are even aiming to conquer the “burger temples” such as McDonald’s or Wendy’s.

If reaching a satisfactory degree of similarity puts an end to the carnivore complaining (around 70% of the beyond burger customers are meat eaters), it means that the arguing about meat alternatives it is purely ideological, between two opposite consumption tribes. Therefore, the argument we started with, can actually be turned upside down:

A hamburger is not a cow anymore, by far. Is much more akin to the dinosaur nugget, which “hides” the chicken from the kids. It helps to conceal its animal origin, it shields us to be exposed to its animal origin, or animal reminder (one of elicitor of disgust), from which the modern consumer is becoming more and more distant. So the strongly flavoured and shaped processed meat and it’s vegan alternative are both equidistant, and quite far, from the “real thing”, their original form.

And that’s’ probably why the faux-meat products are actually not appreciated by more hardcore vegan.

I am just waiting for what my complaining friend will have to say about Lab-grown meat or the new lab grow tuna when they will hit the European market: is that going to be close enough to the real thing?

For further reading check this interesting in-depth article, from Pacific Standard: THE BIOGRAPHY OF A PLANT-BASED BURGER

References

[1] Jacoby, J., Troutman, T., Kuss, A., & Mazursky, D. (1986). Experience and expertise in complex decision making. ACR North American Advances.

[2] Howard, J. A. S., & Jagdish, N. (1969). The theory of buyer behavior (No. 658.834 H6).

[3] Fandos Herrera, C., & Flavián Blanco, C. (2011). Consequences of consumer trust in PDO food products: the role of familiarity. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 20(4), 282-296.

[4] Pliner, P., Pelchat, M., & Grabski, M. (1993). Reduction of neophobia in humans by exposure to novel foods. Appetite, 20(2), 111-123.

[5] Schösler, H., De Boer, J., & Boersema, J. J. (2012). Can we cut out the meat of the dish? Constructing consumer-oriented pathways towards meat substitution. Appetite, 58(1), 39-47.